Today, We Say Goodbye: In Remembrance of Joe Maynen

My husband, David, called one evening in the fall of 2007 to ask if it would be okay to bring over “some guys” he had met at the local board game Meet-Up. He’d been going to the Bolingbrook Barnes & Noble for several weeks, sort of canvassing the gamers crowded shoulder-to-shoulder around its poorly-sized Starbucks cafe tables. The goal had been to find, through these neutral-location gatherings, a “safe” population of new gamer friends, ones he wouldn’t mind knowing where he lives and coming by regularly. (If you are a gamer, like us, be honest. You know this is a good plan. Not all of us are paragons of our kind.) That goal had become especially important as we had just had our first child a few months before and wanted desperately to maintain a social life, but also knew that getting out of the house to do it was going to become much harder. Shifting “going out” to “gathering a gang of people in our basement for weekend gaming, knowing they understood that sometimes, Tracy or David would have to dart off to attend to noises on the baby monitor” seemed the best course.

I said yes, sure, jogging Tiny Corwin against my shoulder and cradling the phone in the other. Bring them by.

“Do you want to know about them?” David asked.

“You’ve been pre-screening for weeks. I trust your judgement.”

They appeared in a small group, all around the same time: John, an affable, articulate, handsome guy finishing pharmacy school. Hector, a wolfishly charming, acid-tongued statistician, to whom I owe the Alchemist’s habit of hanging his spectacles on his shirt collar. And, finally, Joe, whose tall, stoic composure concealed a curated lifetime supply of fart jokes, science fiction references, and puns. He was a nuclear regulatory inspector with the NRC, having cut his chops in nuclear tech through service on nuclear submarines.

It worked out beautifully. We called the group (not without affection, though very much without tact) the Hobos, because their mutual bachelorhood, relative distance from family (Hector’s was down in Texas; John’s in Rockford, Illinois; and Joe’s peppered throughout the nation, with a cluster of them in the northwest suburbs), and regular appearance at our door made me into a kind of unexpected proprietor of a social club and soup kitchen for gamers. They would come over once, often twice in a week, and I’d make a big dinner, and hop in and out of the less brain-burning games sandwiched between their weekend-destroyers.

To help clarify to a growing Corwin, who needed some sense of who these people coming to his home constantly were, we called them the Evil Uncles.

For a long time, we didn’t actually know Evil Uncle Joe’s surname. He was “Puerto Rico Joe” because of his frankly terrifying ability to demolish anyone playing Puerto Rico while simultaneously playing another game over at a neighboring table, back in the Barnes & Noble days. Eventually, probably about three years after meeting him and a few hundred visits to our home, we got around to sheepishly asking for his full name, so we could mail him something.

Joe Maynen.

I focus on Joe here not because John and Hector weren’t important — they were, and still are, though they’ve moved away and started new lives we periodically get to check into. I focus on Joe because last Wednesday, I was visiting him in hospice, wondering if it would be the last time I’d see him alive. Today, just one Wednesday later, I’m digging through my children’s closets for dress shoes that fit, because he is gone, and we are saying goodbye in the way people do, gathering and adjusting and sharing long, shell-shocked stares.

Joe captured Corwin’s first firefly on a warm July night. He helped us move houses, and paint houses, and remodel basements. He wrestled our dogs and made up raps about their deep interior lives (spoiler: these lives are driven mostly by chewing on things) that he would sing to them with the goal of seeing just how cringe-worthy he could make them. He extolled the virtues of the two best characters in Star Wars to our children: Wedge Antilles, the only person to destroy more than one Death Star, and Aunt Beru, because seriously, how awesome is the aunt who gives you blue milk? (If you ask my son who the best character in Star Wars is, he will still look at you like this is a crazy question and feed you Evil Uncle Joe’s argument. He’s eleven now.) Depending on what was served for dinner, he would remind all assembled that he knew a rhyme about beans, and when Corwin or Deirdre would insist on wanting to know it, he would look at them gravely, and say, “It’s not time yet.”

One day when he was about seven, Corwin leaned in across the table to inform Evil Uncle Joe, “I know that rhyme, too,” and the silent look of understanding that passed between them was its own passage into proto-manhood.

My novels wouldn’t exist without Joe. I wrote the first on something like a dare, and had no confidence in its value until I handed Joe part of the manuscript and asked if he would mind reading. Joe was a passionate lover of science fiction and fantasy, but he leaned much more heavily into sf, with Asimov and Clarke and Card ranking among his favorites. Their style wasn’t my style — not even slightly. But that was the point. If someone who had never wanted to read something like what I had created could want more, then maybe, just maybe . . .

The next Saturday, Joe arrived on my doorstep with a smile, and the chunk of ms covered in markings. He asked if I had the next part ready.

It is important to note that Joe was not a believer in polite lies. If you asked him anything directly, he would tell you his feelings directly. Not unkindly, but not with any bandying about, either.

“Did you really like it?” I pressed.

He nodded. “I did. I need to know what happens next.”

And that was what I needed. More than even what came next, Joe wanted the story of the world of The Nine itself: the Unity wars, and what the mercenary group was like when Leyah was still alive, and how Anselm lost his finger. He was hooked.

Joe was my husband’s best friend. They stayed up late, talking baseball, and family, and work, and friends. They debated the merits of various game expansions, the integration of House Rules, and refined the table etiquette for determining what it means to have a Culture rating of less than 10 for your civilization. (This has to do with fart jokes. It always has to do with fart jokes.)

But Joe was also there for me, always. When my mother died, and when the rejections on the novel kept flowing in, first from agents and then from editors. He played Small World with me and bought us all of the expansions as Christmas gifts even though he really didn’t like the game; he knew it was one of my favorites, and “Tracy gets to choose this one” was a mantra for him at a certain hour of any gaming evening I wasn’t swamped with writing or grading. After learning more about the school where I teach and the students there, he set up an automatic donation to our advancement fund — in no small amount — which hit every December, and was specifically ear-marked for the English department.

“Found Family” isn’t just a trope. It’s a reality I’ve been fortunate to live.

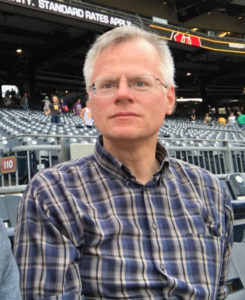

In the late summer of 2017, not too long after the picture shown with this post was taken (at PNC Park in Pittsburgh, where he stopped to meet my husband during our trip to the Nebula Award conference and rescue him from some hob-nobbing by catching a game), a two week period passed where we didn’t hear from Joe at all. This was, to say the least, highly unusual. He wasn’t answering his phone, or his texts, and though we knew him to be deeply private about personal affairs, he was never uncommunicative. He certainly wouldn’t have chosen to be, given the increasing pitch of distress in our inquiries. Finally, we got a text back. Been a bad few weeks. In the hospital. I’ll fill you in, it read, more or less.

A few days later, it was Saturday, and he was back at our dining room table, looking yellow and tired and at least ten pounds lighter than he’d been just a few weeks before.

Cancer. Liver, or maybe someplace else. It was hard to pin down the origin, given how the mass was distributed, and it wasn’t operable. Stage Four. The doctors had given him his odds, because they had to, and they weren’t good. He hadn’t been feeling entirely well in a few months, but had chalked his shortness of breath and low threshold for exhaustion to the fact that he was walking more for exercise and was probably just out of shape. Turns out, there was a baseball-to-softball-sized mass pressing right into his lungs.

Joe kept coming every weekend his health didn’t absolutely prevent it, and our gaming table morphed around a kind of bucket list for him. Trying to play through Gloomhaven. Trying to defeat the undefeated Elder Gods of Arkham Horror and Eldritch Horror. Helping Corwin learn some of his first, really sophisticated games. He’d known the boy since he was only a few months old, after all.

I don’t need to tell you what cancer does to a person. That’s all too well known, and all too visible — the whittling away, physically and emotionally. We saw it in steady increments, week by week, as chemotherapy worked and made progress . . . and then, eventually, didn’t.

I turned in my first complete version of The Fall in January 2018, and worked on editing it through the first week of March. The tide hadn’t turned completely against Joe, by then, and so, having already had his feedback on the text as a work in progress, struggling to find something I could do to help him fight an impossible-seeming fight, I wrote the dedication as follows:

For Joe Maynen, my found family.

You wanted what happened before and got the middle, instead.

Now you have to stay for the end.

I showed it to him before I emailed the manuscript back to my editor and agent. Joe was never one to be at a loss for words, but he was, at least for that moment.

Sometimes, hope doesn’t pay off quite as you intended.

Joe passed away on Saturday, October 20, a little less than three months before The Fall‘s January 15, 2019 release date, and decades before he should have done. I am grateful to my editor and all the staff at Pyr for working to get me a bound copy of the ARC as quickly as possible, so he could hold his book in his hands. He’d had it for about four weeks, and had memorized the dedication, reciting it to some of his visitors in hospital and hospice, by the end. He still had some notes on the manuscript — things he wasn’t a great fan of. All that kissing, for one thing. He was convinced it was in there because “publishing expects her to do that,” but the truth is, I just really wanted certain people to smash faces.

Sorry, Joe.

Grief is a funny thing. There is a hole in my house around six feet tall. It sits in the chair beneath our matted print of Ward Shelley’s “The History of Science Fiction,” right below the curve where Babylon 5 and Space Operas whorl off to meld with Zelazny and Moorcock. It tells stories about the ship systems so critical to the functioning of a nuclear submarine that, if they give way, the ship must return to port for repairs, and how on Joe’s ship, the soft-serve ice cream machine was one of them. It asks me what I’m teaching my students in Speculative Fiction Studies this coming spring — or it would, but I can’t quite hear it, because it’s on the other side of a place I’m not meant to go yet, a place I want to pull it back from, so it can tickle my daughter and wrestle my dog and talk about the World Series with my husband.

I’m not sure if any of us will sit in that chair. At least, not for a long time.

Grief is a funny thing. So is hope. I’m working on the copy edits for The Fall now. If I’m going to change that dedication — make it clear that Joe won’t get to see how this story ends, after all — now is the time to do it.

And I’ve decided I won’t. Those words mattered to Joe. They mattered enough that with what little energy he had left, he memorized them, and repeated them, and marveled at them. They are an artifact of an ambition we shared, something we wanted to make true by believing in it.

In this small way, I’m going to make Joe stay to the end. It’s what I think he would want. It’s what I want. It’s the one thing left I can do.

Addendum:

If you’d like to say thank-you to Joe – for being my friend, my family, my spur moving me forward – you can donate to the Wounded Warriors Project, in Joe’s name as a veteran, or the American Cancer Society, for the sake of others blindsided as he was.